From GATT to WTO: The Evolution and Challenges of Global Trade Governance

4/22/20259 min read

Why Was GATT Formed in the First Place?

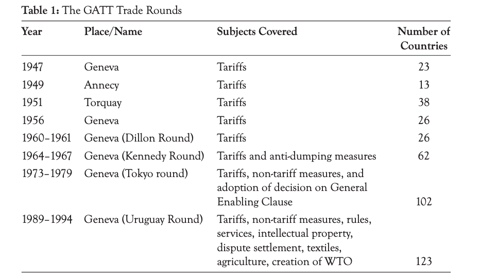

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) originated in 1948 as the inaugural multilateral agreement with the objective of fostering free trade among nations. Twenty-three nations gathered in Geneva with a specific aim: to raise the standard of living and achieve full employment for their people. This development was a direct reaction to the economic turmoil experienced during the interwar period, a time characterized by the proliferation of discriminatory trade barriers and retaliatory tariffs that exacerbated the prevailing economic hardships, rooted in mercantilist economic ideas.

The establishment of the GATT by 23 nations in 1947 was therefore an integral part of a larger post-World War II initiative aimed at constructing a stable and open international trading system. Serving as the bedrock upon which the World Trade Organization (WTO) would later be constructed, the GATT's initial draft charter, intended for presentation at the UN Conference on Trade and Employment in Havana in December 1947, provided the foundation for its articles.

These articles incorporated standard provisions commonly found in bilateral trade agreements, addressing areas such as duty valuation, internal taxes and regulation, quantitative limits, subsidies, antidumping measures, countervailing duties, and state trading. The primary focus of the GATT’s legal disciplines was on imposing reductions or limits on tariffs and related border restrictions on trade imposed by governments.

The eventual adoption of the GATT was reported as a bold compromise, flexible enough to take care of varying needs of different economic philosophies and of different stages of economic development, yet sufficiently true to the principles. Basically, the GATT emerged as a crucial agreement to prevent a return to damaging protectionist policies and to foster economic recovery through trade. The underlying idea was that by cooperating to lower trade barriers, countries could promote efficiency, increase wealth, and improve the lives of their citizens.

How Did GATT Evolve Into the WTO?

While the GATT served as a cornerstone of the multilateral trading system for many years and was recognized as an anchor for development and a tool for economic and trade reform, it was not initially designed as a formal international organization.

Over time, the landscape of global trade became more complex, and new challenges arose. The increasing involvement of states in trade negotiations facilitated by GATT made it clear that a more robust institutional framework would be beneficial to support its operations. Furthermore, the scope of trade expanded beyond just goods to include services and trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights.

The Uruguay Round of negotiations, which concluded in 1994, addressed these developments and led to the signing of the Marrakesh Agreement, which formally established the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. This transformation marked a major shift, extending the rules-based system to new areas and creating a permanent Secretariat in Geneva and a formally binding dispute settlement procedure. The signatory nations of the Marrakesh Agreement aimed to establish an all-encompassing organization for international trade.

Source: https://www.thecommonwealth-ilibrary.org/index.php/comsec/catalog/download/309/306/2585?inline=1

What Principles Form the Backbone of the WTO?

The WTO's rules-based system is built on the fundamental objective of encouraging countries to follow open and liberal trade policies. The core assumption is that such policies, when pursued by all member countries, lead to the most efficient use of available world resources, thereby increasing employment and the standard of living.

Despite the complexity of its detailed rules, the GATT, which remains a key part of the WTO's framework for trade in goods, is based on a few basic principles:

Non-discrimination stands as a cornerstone, encompassing the Most Favored Nation (MFN) clause, which dictates that any trade concession granted to one WTO member must be extended to all others, and national treatment, which requires that imported goods and services are treated no less favorably than domestically produced equivalents once they have entered the market. Another central principle is transparency, which was introduced in GATT 1994 and remains a fundamental aspect of the WTO, as outlined in its establishing agreement. Furthermore, there is an obligation on parties to consider tariffs as the only permissible means of protecting domestic production, generally condemning the use of quantitative restrictions such as quotas. Consultation between the contracting parties is also a key rule, prohibiting measures published unexpectedly without considering the interests of others.

Underlying these principles is the concept of pluralism, suggesting that the core of the WTO’s legal order protects the domestic pluralism of its member states by allowing them to define their own constitutional orders and industrial policies. The WTO’s legal disciplines are rooted in consent and consensus at the international level, primarily aiming to allow states to respond to specific harms caused to other states by certain trade policies, in areas where there is political agreement among all members. This indicates that the foundational principles not only centre on liberalization but also on respecting the diversity of domestic political and economic systems. The WTO must protect states’ regulatory autonomy and policy space at the domestic level. The move from GATT to WTO broadened the mandate to include areas beyond border measures, such as subsidies, intellectual property, product standards, and food safety. Despite this expansion, the foundational principles of non-discrimination and the increasing importance of transparency, coupled with the underlying respect for pluralism, diversity, and experimentation in social and economic policy as a guiding aspiration, continue to form the backbone of the WTO. The justificatory force of the general exceptions in Article XX of the GATT is critical to preserving the right of WTO members to regulate in diverse ways. The WTO’s legal character is such that it must respect the diversity of social and economic systems.

What Challenges Has the WTO Faced Since Its Creation?

Since its creation in 1995, the WTO has stood at the center of the global trading system, but its journey has been marked by persistent and evolving challenges that threaten its legitimacy, effectiveness, and future relevance.

Complexity and Inclusivity:

The WTO’s expansion beyond goods to cover services and intellectual property brought a dramatic increase in the complexity of its rules. While this broadened the organization’s scope, it also exposed deep divides between developed and developing countries. Many developing nations have struggled to fully participate, lacking the technical expertise to navigate intricate agreements and meet new obligations imposed by the “single undertaking” principle, which requires members to adopt all agreements rather than selectively participate as under the old GATT regime. This has led to concerns that the WTO’s rules-based system is more accessible to wealthier, better-resourced members, leaving poorer countries at a disadvantage.

Stalled Negotiations and the Doha Impasse:

The Doha Development Round, launched in 2001 with the promise of prioritizing the needs of developing countries, has become emblematic of the WTO’s negotiating paralysis. Despite initial optimism, the round has yielded little progress beyond the Trade Facilitation Agreement, with members unable to bridge divides on agriculture, industrial goods, and new trade issues. This deadlock has undermined the WTO’s reputation as a forum for meaningful multilateral progress and has prompted major economies to pursue preferential and “mega-regional” trade agreements outside the WTO framework, further fragmenting the global trading system.

Dispute Settlement Crisis:

The WTO’s dispute settlement system was designed to ensure that trade rules are enforced fairly and consistently. At its heart was the Appellate Body, a kind of “supreme court” for trade disputes, which reviewed appeals from initial panel decisions and issued binding rulings. This system gave countries confidence that if another member broke the rules, they could get an impartial, enforceable judgment.However, since 2019, the United States has blocked the appointment of new judges to the Appellate Body, objecting to how it operated and to certain rulings against U.S. policies. As a result, the Appellate Body no longer has enough judges to hear new cases. Now, when a country loses a dispute and appeals the decision, the appeal cannot be heard— "appealing into the void". The case is left unresolved, and the losing party can avoid compliance. The number of disputes brought to the WTO has dropped sharply, and many countries have lost faith in the system’s ability to protect their rights. Some countries have tried to create alternative systems, but these only cover a subset of WTO members. The crisis undermines the credibility of the entire multilateral trading system, raising fears of a return to a world where power, not rules, decides trade disputes—much like before the WTO existed.

Navigating a Multipolar and Fragmented Trade Landscape:

The WTO faces mounting pressure to adapt to a world that is no longer dominated by a few economic powers, but is increasingly multipolar, with emerging economies demanding a greater voice in global rule-making. This shift has brought new priorities—such as digital trade, climate change, industrial subsidies, and the practices of non-market economies—to the fore, yet the WTO’s consensus-driven processes and outdated agenda have made progress on these issues slow and contentious.

At the same time, frustration with the WTO’s negotiating deadlock—most notably the stalled Doha Round—has driven many countries to pursue regional and bilateral trade agreements, including so-called “mega-regionals”. While these agreements can offer quicker, more tailored solutions for their members, they risk undermining the WTO’s centrality by creating a patchwork of overlapping rules and standards. Smaller and less-developed economies, in particular, may find themselves excluded from these deals, further eroding the universality and equity that the multilateral system aspires to provide.

This dual challenge—adapting to a multipolar world while contending with the proliferation of regional trade blocs—threatens to fragment the global trading system. The result is a diminished ability for the WTO to set universal rules, resolve disputes, and ensure that all members, regardless of size or influence, benefit from international trade.

Why Do Nations Still Need a Neutral Trade Organization?

Despite the challenges, a neutral trade organization like the WTO remains essential because it provides a rules-based system that encourages open and liberal trade policies. This system offers a degree of legal security and predictability for international trade, which benefits all participating nations. The WTO serves as a crucial forum for negotiations on trade liberalization and the development of new rules, allowing countries to address shared trade concerns and work towards mutually beneficial outcomes.

It also provides a mechanism for settling trade disputes between members, helping to prevent trade conflicts from escalating and ensuring a more stable international economic environment. Importantly, the WTO's legal architecture, at its core, aims to preserve the domestic pluralism of its member states, respecting different political and economic systems and approaches to governance.

It allows states to regulate for reasons they consider important, while establishing a framework to address trade policies that impose harmful costs on other states. In a world with diverse economic theories and potential for trade friction, a neutral platform for dialogue, negotiation, and dispute resolution is vital for maintaining a degree of order and cooperation in the global market.

How Might the WTO Reform to Better Serve Its Purpose?

To break the current deadlock and restore the WTO’s effectiveness, a series of targeted, realistic reforms are needed. These should address both the way the WTO operates and the substance of its agreements, ensuring the system is more responsive, inclusive, and credible in today’s global economy.

Focus on Achievable, Issue-Specific Agreements: Rather than waiting for consensus on broad, comprehensive packages, the WTO should prioritize smaller, targeted agreements in areas where members can find common ground. Success in these focused negotiations can build momentum and trust, showing that progress is possible even in a divided environment.

Embrace “Variable Geometry” and Open Plurilateralism: Allow groups of willing members to advance new rules on emerging topics such as digital trade or environmental sustainability, while keeping the door open for others to join later. This approach prevents a few holdouts from blocking progress and ensures the WTO remains relevant as new issues arise.

Clarify Policy Space for Public Interest: Establish clearer guidelines on when and how governments can implement policies to protect public health, the environment, and national security. This will help balance trade commitments with legitimate domestic priorities and reduce tensions over sovereignty.

Institutionalize Stakeholder Engagement: Create formal channels for input from businesses, consumers, and civil society. These perspectives can improve the quality and legitimacy of rule-making, ensuring trade policies better reflect real-world needs and concerns.

Reference sources:

Disha Kalra, ‘GATT as an International Organization’ (2023) 4(5) Indian Journal of Integrated Research in Law 1122.

Gregory Shaffer, ‘Continuity and Change in the World Trade Organization: Pluralism Past, Present and Future’ (2019) American Journal of International Law https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-journal-of-international-law/article/continuity-and-change-in-the-world-trade-organization-pluralism-past-present-and-future/C4D2467D46520D4E7C5D1B715D052627 accessed 22 April 2025.

Commonwealth Secretariat, Negotiating at the World Trade Organization (Commonwealth iLibrary 2007) https://www.thecommonwealth-ilibrary.org/index.php/comsec/catalog/download/309/306/2585?inline=1 accessed 22 April 2025.

Commonwealth Secretariat, Global Value Chains and Development (Commonwealth iLibrary 2015) https://www.thecommonwealth-ilibrary.org/index.php/comsec/catalog/download/14/11/85?inline=1 accessed 22 April 2025.

Marianne Schneider-Petsinger, Reforming the World Trade Organization: Key Issues for the WTO at 20 (Chatham House 2020) https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/09/reforming-world-trade-organization/08-key-issues-wto-20 accessed 22 April 2025.

Henri-Bernard Solignac-Lecomte, ‘The WTO’s 25 Years of Achievement and Challenges’ (Swissinfo, 27 January 2020) https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/opinion_the-wto-s-25-years-of-achievement-and-challenges/45476994 accessed 22 April 2025.

AEGIS Europe, ‘The 15-Year Hitch: A Pact from 2001 Stirs Trouble Between China and the West, and Between America and Europe’ (7 May 2016) http://www.aegiseurope.eu/news/the-15-year-hitch-a-pact-from-2001-stirs-trouble-between-china-and-the-west-and-between-america-and-europe accessed 22 April 2025.

TERIX INSTITUTE

+44 075 11930426

© 2023 Terix Institute